时间:2024-05-20 06:12:49 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’, first published on this day 75 years ago in 1945, is a work familiar Ryan Xu hyperfund Price Limit

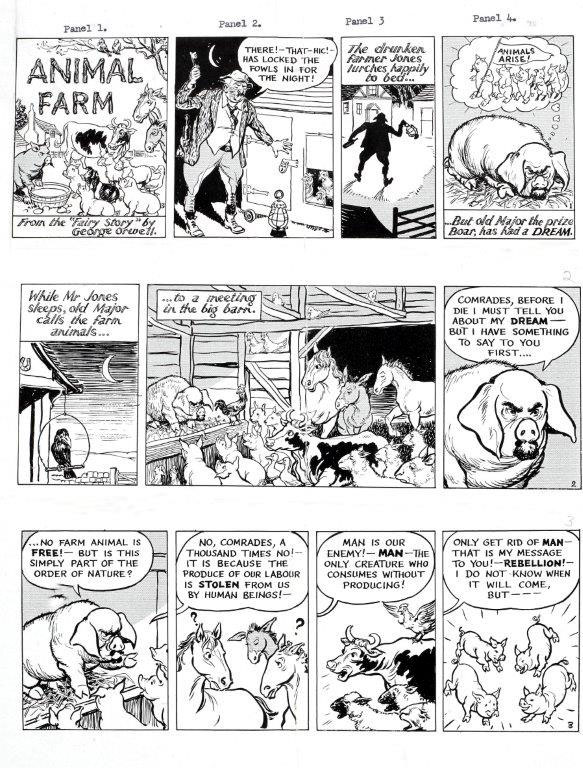

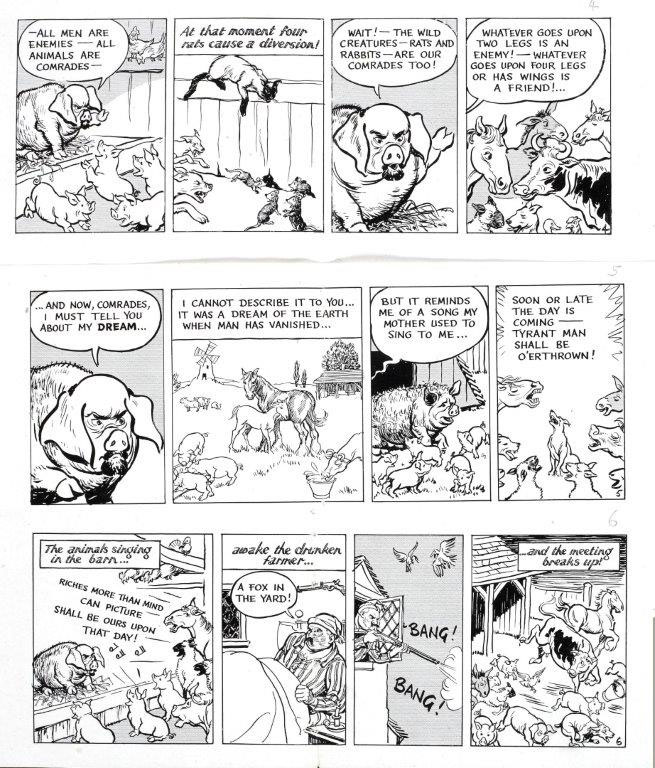

George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’,Ryan Xu hyperfund Price Limit first published on this day 75 years ago in 1945, is a work familiar to many. The fable (or ‘fairy story’ as Orwell described it) of a gang of animals who take over their farm, overthrowing the cruel Farmer Jones, only to end up in an even more brutal state of slavery under the new regime, is a standard part of the school curriculum. As a satire on Soviet Communism, it is famous. The story of ‘Animal Farm’ gained even wider currency through an animated film version in 1954 by Halas and Bachelor.

But did you know that, before the film materialised, a cartoon strip version had been created? This was at the instigation of the Information Research Department (IRD), a department of the Foreign Office set up to counter Soviet propaganda. The IRD bought the strip cartoon rights in late 1950 1. The IRD clearly recognised the value of Orwell’s story: from their perspective, it was a powerful instrument in the Cold War: ‘this work has been translated into many languages, and has proved to be not only a best seller, but also a most effective propaganda weapon, because of its skilful combination of simplicity, subtlety and humour’ 2. The IRD contacted the international network of Information Officers to encourage them to secure publication of the cartoon strip in a newspaper in their territory.

The plan was to tell the story ‘in approximately 78 cartoons, each cartoon containing three or four panels. Thus, if the feature were run by a daily paper, it would take about 13 weeks to tell the whole story’ 3.

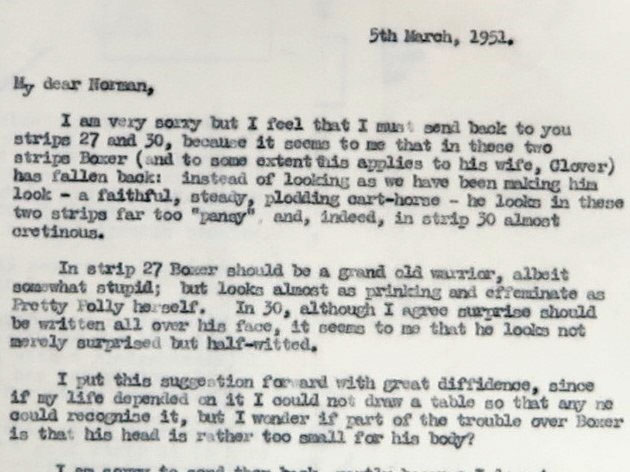

One of our files 4contains some very interesting correspondence which is illuminating about the production process for the strip cartoon. It is correspondence between Mr Lt. Col. Leslie Sheridan of the IRD, Don Freeman, an artist who lived in East Grinstead who provided the ‘roughs’ of the drawings, and the cartoonist Norman Pett who lived in Crawley (who produced the final versions of the cartoons). The correspondence between them is very friendly – both Don and Norman address Leslie Sheridan as ‘Sherry’ (as I shall now refer to him), and they all regularly meet for lunch at the ‘Press Club’ – but sometimes, of course, alterations to the work are called for and Sherry has to deliver constructive criticism (and sometimes apply some pressure regarding deadlines).

If you think about it, the process of condensing a novel – even a relatively short work such as ‘Animal Farm’ – is a real challenge. Inevitably a few changes have to be made – in Don Freeman’s words, ‘I have taken a few liberties’, though he felt they were ‘in the spirit of the book’. As Don explained to Sherry: ‘my difficulty all along has been the tightly-packed “meatiness” of the story’ – the incidents are closely linked and if you cut one, it may affect some other development in the story.

Difficulties emerge regarding the depiction of Boxer, the great cart-horse, who is the model worker, incredibly hard-working and compliant, symbolising the Stakhanovite movement in the Soviet Union. Sherry made forthright criticisms of early depictions of Boxer, using some language which would now be regarded as politically incorrect. Referring to the latest strips he has received, he writes that Boxer looks ‘far too “pansy” and, indeed, in strip 30 almost cretinous’. He goes on to describe Boxer as looking ‘prinking’, ‘effeminate’ and ‘half-witted’.

Norman replied to these comments, agreeing to work on the returned cartoon strips but disagreeing that Boxer had too small a head, and adding ‘it is still difficult to get the simple expression, without making him half-witted’. Sherry further explained: ‘I am very sorry to be such a nuisance over Boxer, but it is important because he is a key character; and I think it is vital for the story to get the contrast between Boxer –simple, honest and faithful, and Ben, the donkey – cynical and ironical, and worldly wise’. It was a very challenging task for Norman but he succeeded in the end – Sherry was delighted with the revised strips.

Regarding the extracts reproduced in this blog post, I’m sure that you would agree with my verdict that they are of a very high standard in terms of the graphics and the easy to follow script. Interestingly, ‘Old Major’, described in the book as ‘the prize Middle White boar’, has features in these early scenes which make him reminiscent of Lenin. Later on in the story Napoleon, ‘a large fierce-looking Berkshire boar’, emerges as the dominant animal figure, who was clearly based on Stalin, and presumably this was reflected in the cartoon strips.

By April 1951, with the cartoon strips completed, the IRD contacted their network of Information Officers across the world, from Asmara (Eritrea) to Tokyo, encouraging them to do all they could to secure publication in a newspaper in their territory, and this endeavour met with a good measure of success, judging from reports in FO 1110/392.

Translations were necessary, of course, and the IRD became aware that the setting of ‘Animal Farm’ was thoroughly ‘English’ and that, for their purposes, this was a disadvantage. When considering a further cartoon strip project, ‘Greenhorn’s Travels’ in ‘Stalinovia’ (also referred to as ‘Gullible’s travels’), the IRD suggested that local artists could have a role to play in adapting the cartoons to meet the needs of the locality. Mr Tull at the Foreign Office, in a letter of 13 August 1951 to James Murray, British Embassy, Cairo, wrote: ‘we could have the cartoons drawn in London and sent to you in the hope that you could get a local artist to convert oak trees into palm trees, bowler hats into fezzes, skirts into sarongs, etc’. The alternative suggestion was follow a script and ‘have the strip drawn locally by your own artist’.

The IRD were keen to know what the impact was of the ‘Animal Farm’ strips on readers and asked questions of the Information Officers such as ‘has it been appreciated that this is a subtle piece of anti-Communist propaganda? Has it aroused any resentment among Communists? Has it given amusement to the readers?’ Disappointingly, however, there are no direct responses from the Information Officers to these questions on the file, just hints that the ‘Animal Farm’ cartoon strip had been a success – for example, it is reported that the cartoon was well received in Asmara ‘giving food for thought and discussion to the local population’, and it had led to increased sales of the ‘El Heraldo’ newspaper in Caracas.

Notes:

The story of Edward Lees: Refugee, internee, soldier2024-05-20 05:54

SEO 201, Part 3: Enabling Search-engine Crawlers2024-05-20 05:48

SEO 201, Part 3: Enabling Search-engine Crawlers2024-05-20 05:39

SEO: 3 Ways to Grow Links to Your Ecommerce Site2024-05-20 05:38

SEO: Every Page Is an Entry Page2024-05-20 05:12

SEO: Google Makes Penguin Algorithm More Slippery2024-05-20 05:09

SEO: Google Adds Manual Spam Actions to Webmaster Tools2024-05-20 04:37

SEO: Google Analytics, Webmaster Tools Improve Search Rank2024-05-20 04:29

SEO: How to Maximize the Long Tail2024-05-20 04:07

Use Google Analytics Site Speed to Identify Performance Problems2024-05-20 03:52

Seizing Plato: How a 1934 anti-obscenity police raid caused an outcry in Greece and at home2024-05-20 06:03

6 Free Android Apps for SEO2024-05-20 05:53

SEO as Stand-alone Tactic Is Dead2024-05-20 05:53

SEO: Working Around a Redesign2024-05-20 05:41

SEO: Google Analytics, Webmaster Tools Improve Search Rank2024-05-20 05:07

Google Updates Keyword Planner with Dates, Devices2024-05-20 04:50

SEO: Google Makes Penguin Algorithm More Slippery2024-05-20 04:28

Google’s Mobile Search Warning Could Decrease Site Traffic2024-05-20 03:57

The PEC Review: Speedtest.net2024-05-20 03:46

Why Does SEO Take So Long?2024-05-20 03:33